Lessons from Jonestown

Conversation

As a part of National Hazing Prevention Week, we will be sharing content that touches upon many aspects of hazing awareness, education, and prevention. This will range from pointing out the logical fallacies of hazing defenders to highlighting the decision-making that preludes men and women blithely abusing each other. Some of this content will be new and some of it will be republished from Sigma Nu's nearly 150 years of being committed to anti-hazing. At the end of each piece we will note the author and date of original publication, if applicable. We hope these pieces spark conversations in chapter house living rooms, campus cafeterias, locker rooms, and the myriad of other places where the discussion of anti-hazing needs to happen between brothers, sisters, friends, and teammates.

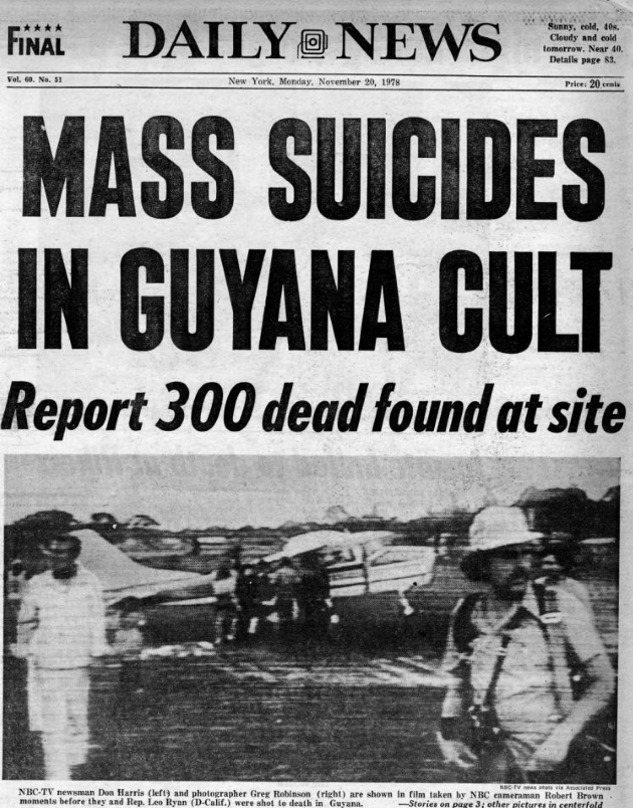

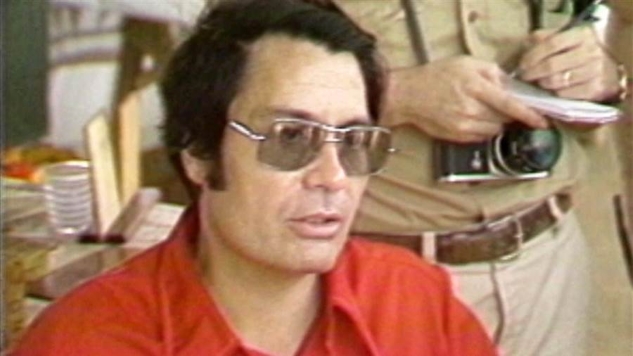

I watched a documentary on Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple last weekend and couldn’t help but relate some of the underlying causes to fraternity life. No, I’m not suggesting that fraternity life is becoming a socialist utopia turned forced-labor camp; comparing is not equating and few analogies are perfect. But attempting to understand why 909 people were convinced by a toxic leader to commit mass suicide holds lessons on how groups of good people can make bad decisions. Here are a few of the parallels:

1. Total denial of reality

Throughout the documentary members of the Peoples Temple repeatedly claim, “[Jonestown] is heaven on Earth,” or “I’ve never been so happy in my entire life.” This false sense of reality continued even to the day Jones ordered his followers to inject their children with cyanide-laced kool-aid, just before committing their own suicide.

For some reason student leaders tend to overestimate the current performance of their organization. I’ve heard too many times, “Everything is going great, couldn’t be better,” from a chapter with lousy grades, low numbers, no campus involvement and multiple hazing investigations. Identifying and acknowledging a problem is the first step to becoming an excellent chapter.

If personal servitude is the core philosophy of your chapter’s candidate education program but you’ve convinced yourself it’s not hazing (and you tell everyone “we’re a non-hazing chapter”) then you are denying reality.

It’s no coincidence that the All Chapter LEAD Session on Accountability includes “See It” and “Own It” in the four-step model.

2. The dangers of good intentions

We’ve all heard of the famous road paved with good intentions. Jim Jones preached about peace, justice, equality and other such virtues during service at the Peoples Temple. Sounds good, right? Who wouldn’t be for justice and treating people fairly? On the surface Jones preached the virtues of the Bible, but it quickly became apparent (evidently not for the church’s members) that he maintained a deeper agenda: absolute control over his followers.

Jones even cajoled members into donating their life savings to the church. People sold their homes, cashed in their retirement savings, quit their jobs and turned all belongings over to the collective. In turn, members were provided with food, health care, housing and a community of people for life.

Were members of The Peoples Temple more gullible than the average person? Did Jim Jones prey upon the poor and undereducated? Maybe, maybe not. Either way, the ash heap of history contains countless groups of perfectly sensible people who were duped into bad decisions (or even suicide, in this case) by the allure of good intentions.

Ask any Marshal the goal of his candidate education program and you’re sure to get this answer: “We want the candidates to bond together, learn the history, and prove they’re worthy of initiation.” Who could argue with that? We can’t just initiate anyone, right? Isn’t a brotherhood supposed to bond?

But what happens when “learning the history” becomes public quizzing sessions of arbitrary yelling? Or when “proving you’re worthy of initiation” becomes running errands for brothers or completing other arbitrary tasks? Or when “candidate class bonding” becomes public embarrassment or even worse? Watch out for the bait-and-switch of good intentions for other hidden agendas.

Hazing is often perpetuated under the guise of good intentions: bonding, building better men and teaching history. But the new student leader isn’t falling for it any longer. The emerging student leader recognizes hazing for what is is: a system for deadbeat brothers to gain unearned respect and a source of entertainment for the others. Deadbeat members should be asked to leave, and those who joined to be entertained should reread their candidate Ritual ceremony.

3. Waiting for disaster to acknowledge the need for change

How many times have we seen a community “come together” in the wake of some tragedy? Why should it take the preventable death of a student for the Greek life community to put the rivalries aside and support each other? Why do some chapters only understand the connection between risk reduction guidelines and valid insurance until after tragedy strikes?

Once Jim Jones moved his Peoples Temple from northern California to Jonestown, French Guiana, it should have become clear that something wasn’t right. But the members continued to deny reality and accepted Jones’ sermons as absolute truths.

Jones became increasingly authoritarian, irrational and hysterical; his sermons shifted from discussions of equality and justice to instilling a constant sense of fear among the members. The collective utopia started to look more like a forced-labor camp than the promise land.

Other members of The Peoples Temple must have known about the giant stash of cyanide. Jim Jones even held trial runs of his plans to commit mass suicide. But no one said anything until it was too late.

Lessons learned?

So what does this extreme example of groupthink and mass delusion have to do with fraternity life? While we aren’t headed for the mass hysteria that ended in a tragedy like Jonestown, we can recognize that groups of intelligent college men are capable of making bad decisions–albeit on a much smaller scale.

By now you’ve probably realized the origin of the popular phrase, “Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.” Next time your chapter is coalescing around a bad idea, you be the one to recognize it and do something about it. Don’t drink the hazing Kool-Aid.

Nathaniel Clarkson (James Madison)

Originally Published February 3, 2010